18

19

12

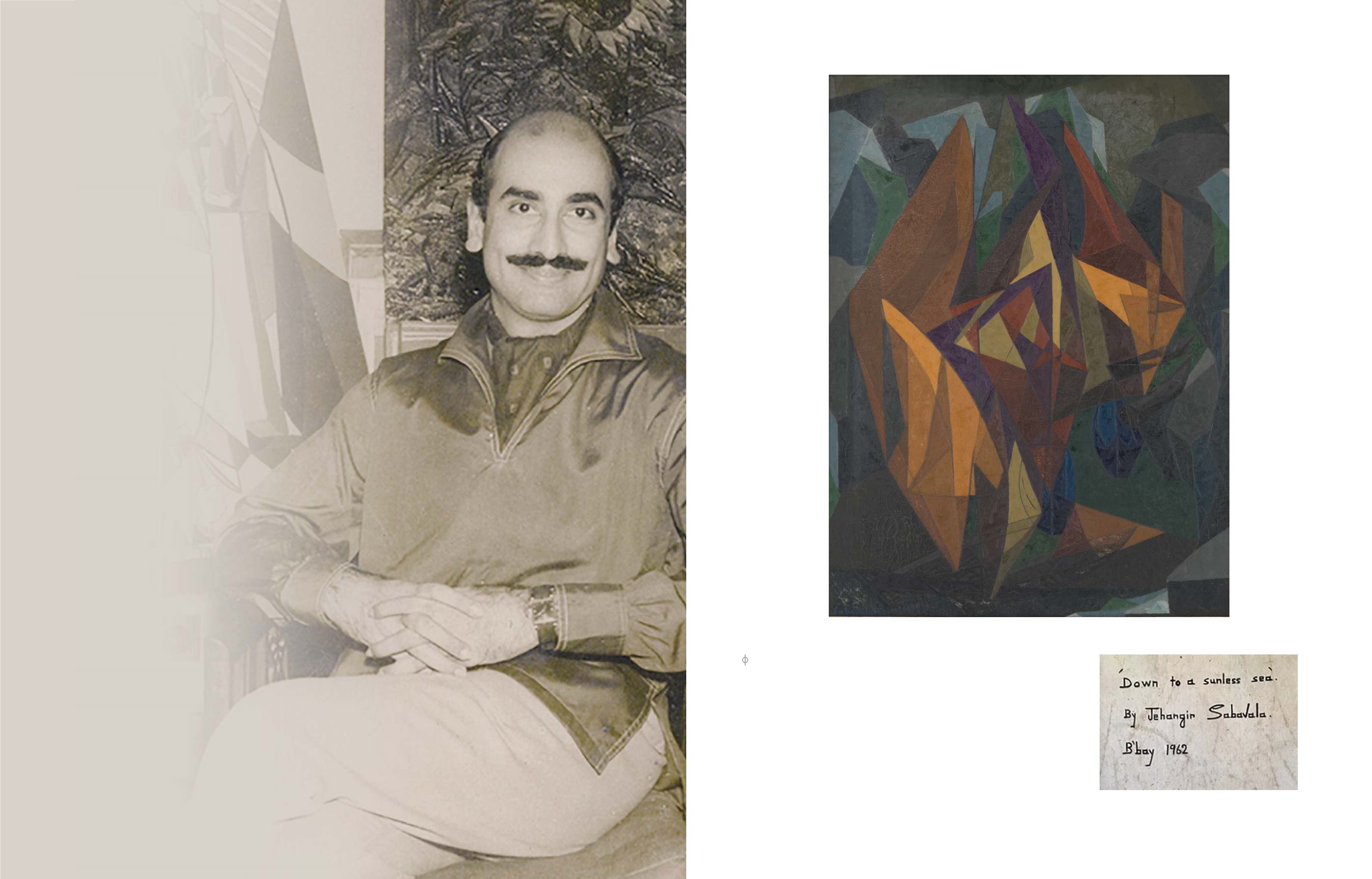

JEHANGIR SABAVALA

(1922 ‒ 2011)

Down To A Sunless Sea

Signed and dated ‘Sabavala 62’ (lower left) and inscribed ‘’Down to

a sunless sea’ / By Jehangir Sabavala / B’bay 1962’ (on the reverse)

1962

Oil on canvas

39.25 x 29.25 in (100 x 74 cm)

Rs 50,00,000 ‒ 70,00,000

$ 74,630 ‒ 104,480

PROVENANCE:

Private Collection, USA

Private Collection, UK

Inscription on the reverse of the painting

The present lot was painted in 1962, which saw the culmination of

the Cubist idiom that Sabavala had explored for a decade since his

return from Paris. Titled

Down To A Sunless Sea

, Sabavala borrows a line

from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famous poem

Kubla Khan

. The poem,

conceived by Coleridge supposedly in an opium‒induced dream,

describes the landscape of Xanadu, the capital city in the kingdom of

Kublai Khan, a great Mongolian emperor in the 13

th

century. In Kublai

Khan’s walled kingdom, flows the river Alph, running through dark

caverns and down to the lifeless sea:

“In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure‒dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea . So twice five miles of fertile ground With walls and towers were girdled round; And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense‒bearing tree; And here were forests ancient as the hills, Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.”The poem further expands on the tumultuous aspect of nature from

which the river is born, contrasting it with the serene, constructed garden

of Kublai Khan’s domed palace. Using vivid imagery, Coleridge paints a

fantastical landscape alluding to the power of intense imagination and

creativity, which come together beautifully in the utopian Xanadu.

The present lot is quite likely Sabavala’s pictorial (and metaphorical)

interpretation of this poem which presents the imagery of the sunny

dome, the icy caves and the tempestuous river in Sabavala’s own

unique interpretation of the Cubist idiom. In the artist’s landscapes in

the early 60s, “Man lives and floats in a far more extended and larger

world than we normally envisage.” (Artist quoted in Ranjit Hoskote,

Pilgrim, Exile, Sorcerer: The Painterly Evolution of Jehangir Sabavala

,

Mumbai: Eminence Designs Pvt. Ltd., 1998, p. 92) As he broke away

from Cubist formalism, the sharp angularities of Sabavala’s paintings

softened and became multi‒faceted, made sublime by strokes of

illumination. According to the poet Adil Jussawala, “The bleached light

Sabavala presents us so frequently is the Indian light, honestly recorded,

and I will admit that it is only after seeing Sabavala’s paintings that I have

been struck by qualities in the light which I would not otherwise have

appreciated. But, as a whole, the landscape in each painting appears to

be governed by a force that exists not in the objective landscape but

in the painter himself... Its origins lie, I think, in literature, in the poetry

of spiritual desolation, of purgatory, of the after‒life, and of

angst

.” (As

quoted in Hoskote, pp. 90‒91)

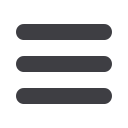

Jehangir Sabavala

Image courtesy of Shirin Sabavala